Launching my Tech Blog

2009/05/21 12:28 PM

I’ve just launched my tech blog. I keep running into topics that I don’t want to put in my personal blog, so I decided to launch something separate.

Click here to see it or you can get at it from the top of the page.

It also has an independent RSS feed, which you can get on the page itself.

Click here to see it or you can get at it from the top of the page.

It also has an independent RSS feed, which you can get on the page itself.

Framing and Forces Part 1: Frames

I have a variety of thinking tools that I use to analyze problems, many of which I’ve mentioned in previous postings. In preparing a future posting, I realized that I should probably write up one thinking tool in more detail, since I intend to use it there.

The tool I have in mind is what I call my “Framing and Forces” tool. This tool is a combination of two other tools, which I’ve found to work well together. The first is the “Frames of Action” map taught in Leadership Calgary and the second is the concept of “Forces” as described the book “The Art of the Long View”, which I’ve talked about before.

This posting will talk about the Frames of Action and a second posting will talk about forces.

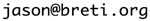

Frames of Action was designed by Ken Low from the Action Studies Institute. It is used as part of the Leadership Calgary curriculum (and used here with permission from Ken).

The term “Frame” refers to a particular level of focus. The diagram is built to keep your attention on several different levels of focus. We often pay attention to only one or two different levels and even then inconsistently and at different times. This tool helps you to be aware of what frames you and others are using. The concept of frames drives your understanding towards how you see others acting and how they see themselves acting. It also explains what they (or you) cannot see because they (or you) are focusing on other things, or on an inappropriate frame for the problem at hand.

You can use this tool to think about your own frames: your family, department, country, government, school board, or any other organization. It’s very versatile.

Below is a blank diagram of all the frames. Click for a larger version.

I think an example might be helpful. A company has overall goals to make money in a certain market segment, defined by their strategies (Strategic Frame). They decide that they need two different divisions “A” and “B” in order to achieve this, so they create those divisions. Each of these divisions has some common Operations Frames (because they work in the same company) but some independent ones as well. Other divisions like Finance, Legal and Human Resources have their own Operations Frames, though also share some with A and B.

You can probably see how this diagram can be used to show conflict. For example, if divisions A and B are in competition with one another for some reason (like bonuses for completed jobs from corporate), they might not be inclined to cooperate with each other. In adversarial companies they might even be “forbidden” to talk to each other or be physically separated to discourage communication. These are examples where divisions are operating in two different conflicting tactical frames, or even two completely opposed operations frames. This is usually not healthy for a company, but it is sometimes done with “startup” divisions that are isolated away from the main company in order to do some unique work. This may or may not be good for a company, but that is another discussion.

There are two other frames that are less well known but are just as important.

You often will not use all frames when drawing a Frames and Forces diagram, but it doesn’t hurt to at least list them on the diagram to jog your memory to see if they are involved in the problem you are trying to solve.

The next posting in this series will talk about Forces and provide an example.

You may like to see the mindmap that was used to write the draft of this series of entries. Please click on the map below for a bigger picture.

The tool I have in mind is what I call my “Framing and Forces” tool. This tool is a combination of two other tools, which I’ve found to work well together. The first is the “Frames of Action” map taught in Leadership Calgary and the second is the concept of “Forces” as described the book “The Art of the Long View”, which I’ve talked about before.

This posting will talk about the Frames of Action and a second posting will talk about forces.

Frames of Action was designed by Ken Low from the Action Studies Institute. It is used as part of the Leadership Calgary curriculum (and used here with permission from Ken).

The term “Frame” refers to a particular level of focus. The diagram is built to keep your attention on several different levels of focus. We often pay attention to only one or two different levels and even then inconsistently and at different times. This tool helps you to be aware of what frames you and others are using. The concept of frames drives your understanding towards how you see others acting and how they see themselves acting. It also explains what they (or you) cannot see because they (or you) are focusing on other things, or on an inappropriate frame for the problem at hand.

You can use this tool to think about your own frames: your family, department, country, government, school board, or any other organization. It’s very versatile.

Below is a blank diagram of all the frames. Click for a larger version.

The frames are broken down into several different types. Not all of them are worthy of your attention at any particular time. That depends on the situation. The frames that most people are familiar with are the following (in order from general to more specific):

- Strategic Frame - This frame deals with planning the strategy that is needed. Here you set up your plans for deploying your solution or approach. As with the name, this frame deals with overall strategy.

- Operations Frame - This frame deals with the creation of common patterns that you use to implement your strategies (“the doing of the strategies” ). Often this is where processes are created, or simply things you regularly do in order to get the job done or problem solved. It might include training, logistics, ways of doing things, hierarchical roles and responsibility. As with the name, this frame deals with the doing of day-to-day operations.

- Tactical Frame - This frame deals with the steps needed in order to accomplish a specific goal. The term “tactic” is used here to refer to something specific, like a specific project or goal. This could be winning a certain objective, delivering a certain product, and so on.

- Sub-Tactical Frame - Below tactical frames are any number of sub-tactical frames, which are used to accomplish tasks for the greater tactical goal. These can be smaller tasks of any sort. It’s often not useful to list them unless they are in some way creating problems at a higher frame.

I think an example might be helpful. A company has overall goals to make money in a certain market segment, defined by their strategies (Strategic Frame). They decide that they need two different divisions “A” and “B” in order to achieve this, so they create those divisions. Each of these divisions has some common Operations Frames (because they work in the same company) but some independent ones as well. Other divisions like Finance, Legal and Human Resources have their own Operations Frames, though also share some with A and B.

You can probably see how this diagram can be used to show conflict. For example, if divisions A and B are in competition with one another for some reason (like bonuses for completed jobs from corporate), they might not be inclined to cooperate with each other. In adversarial companies they might even be “forbidden” to talk to each other or be physically separated to discourage communication. These are examples where divisions are operating in two different conflicting tactical frames, or even two completely opposed operations frames. This is usually not healthy for a company, but it is sometimes done with “startup” divisions that are isolated away from the main company in order to do some unique work. This may or may not be good for a company, but that is another discussion.

There are two other frames that are less well known but are just as important.

- Foundation Frame - Above the strategic frame, this frame talks about the “story” of “what we’re all about”. It describes communities that an organization resides within and how it relates to those communities. These communities both allow and limit freedoms, provide opportunity for responsibilities and specify obligations. A computer company works with several foundation frames, such as what they do (and do not do) relative to other companies and competitors, the physical communities they exist within, including laws, culture, their employees and ways of doing business. A religious organization or charity also operates within many such frames. In fact, we all do as contributors to and people who benefit from society. Many ethics policies in companies, specified as partly strategic frame and operations frame documents, are written to abide within principles at the foundation frame level.

- Transcendent Frame - Above the foundation frame, this frame is the “story” of our connection with existence and life. Despite the title, “transcendent” does not imply any religious or mystical connotation, though many religions do make strong connections with the transcendent frame. When we talk about essential wisdom, philosophy or experience from the past, this falls within the transcendent frame. Some environmental groups talk of protecting the planet for ourselves or for the future. They are describing a transcendent frame that promotes the continued existence of all life on the planet. An example of a company that directly connects their work to the transcendent frame is Ray Anderson’s Interface Inc, which plans to make the company 100% sustainable, and is actively working towards that difficult goal.

You often will not use all frames when drawing a Frames and Forces diagram, but it doesn’t hurt to at least list them on the diagram to jog your memory to see if they are involved in the problem you are trying to solve.

The next posting in this series will talk about Forces and provide an example.

You may like to see the mindmap that was used to write the draft of this series of entries. Please click on the map below for a bigger picture.